L. C. Tatebe1, S. Speedy1, S. Regan3, A. Boone1, F. Cosey-Gay2, L. Stone3, M. Shapiro1, M. Swaroop1 3University Of Illinois At Chicago,CeaseFire Chicago,Chicago, IL, USA 1Northwestern University,Trauma/Critical Care,Chicago, IL, USA 2University Of Chicago,Chicago, IL, USA

Introduction: The paucity of trauma centers in the south side of Chicago leads to prolonged transport times and increased morbidity and mortality for those affected by penetrating trauma. An evidence-based community-driven Trauma First Responders Course (TFRC) could potentially mitigate this effect, but does not currently exist. Bystanders are present at 60-97% of traumas and are more likely to assist with prior training. However, the bystander effect remains a major barrier. We hypothesize that by utilizing the Health Belief Model as a framework, we can characterize the factors in our community that lead to bystander non-interference. Through this, neighborhood focus groups will facilitate effective course development and thus improved patient outcomes and community empowerment.

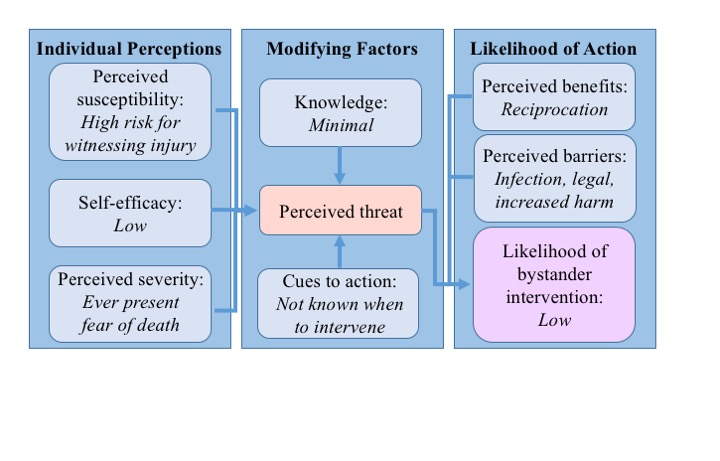

Methods: The Health Belief Model determines the likelihood of an action by examining individual perceptions of susceptibility, self-efficacy, and severity of a health issue, then applying the modifying factors of knowledge and cues to action. The resulting perceived threat is then modulated by perceived benefits and barriers of performing the action. Written surveys and focus group questions were developed to specifically address each of these facets. Focus groups were conducted by 2 guides over an hour with 8-10 community members, including youth at highest risk for violence and key community leaders. Data were collected via surveys and recordings and analyzed quantitatively as well as qualitatively.

Results: The focus groups demonstrated consistency across many of the factors examined, see Figure. Participants felt the perceived susceptibility for witnessing an injury was high. Half stated they worry that they or someone they know will get hurt "a lot" or "all of the time" and that they are "unsure," "not confident," or "not at all confident" in their ability to render aid, demonstrating a sense of low self-efficacy. Only 39% of responders stated they had any form of first aid training, and less than 10% stated they had advanced training. A majority said they did not know when to intervene, which often stemmed from a concern that interference would lead to increased harm. There was significant fear of social or legal retaliation for helping a victim of violence, while 92% would want a stranger to help if they or someone they know was injured. Overall, the likelihood of bystander intervention was deemed to be low.

Conclusion: Critical factors have been identified through the structure of the Health Belief Model that contribute to bystander non-intervention in our community. These will need to be addressed during the development and implementation of an effective TFRC to empower community members to overcome the bystander effect.